?Music means to me eternal life, freedom, the extreme expression. I’ll die without music. Music kills the barriers and lifts the soul to a very, very high degree.?

?Music means to me eternal life, freedom, the extreme expression. I’ll die without music. Music kills the barriers and lifts the soul to a very, very high degree.?

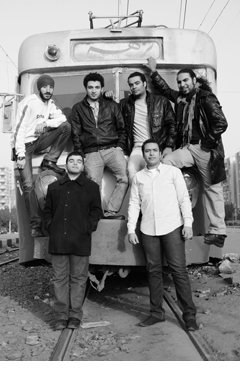

Cairo musician Ousso

Recently, Nour Eldin Nageh Ali, composer and vocalist for the Lel Wa Ain band in Cairo, took the time to talk with Wanda Waterman about his personal musical development, the band, and the effect of the 2011 revolution on the Egyptian music industry. See the first part of this article here.

Prior to the ?Day of Rage,? Nour had fought long and hard to make a niche for himself in the commercial recording industry, composing songs for big music studios. But when one studio wouldn’t pay him for some of his material that they’d recorded, it left a bad taste in his mouth. He began moving in a new direction.

In the beginning it wasn’t easy to persuade good musicians to take a big risk and strike out on their own. ?My start was actually in 2008,? remembers Nour. ?I started my band with an oud player and drums. I tried to recruit other musicians, but everyone wanted a big record contract. I waited for around three years to make the band I have now. Like the other independent bands, we had to build a base of supporters for our music.?

Nour’s disappointment with the commercial music world paved the way for his rapid acceptance of the kinds of new music business models that are now springing up all over the world. Just as in North American folk music circles we see ingenious ideas being implemented to replace the traditional recording contract, so also the Egyptian musical world is learning to find ways to support alternative music by means of audience support. This allows the proceeds of CD and ticket sales to remain largely within the pockets of the musicians themselves.

But in order to make this work, you need to have a fan base.

The 2011 political revolution in Egypt had significant cultural repercussions. There had long existed an underground music scene in Egypt, but its lack of widespread support kept it from thriving or having any marked influence on the culture at large.

?I don’t think Egyptian music changed in response to the revolution,? Nour says, ?but more ordinary people started listening to underground music.?

Lel Wa Ain, like other independent musicians and groups that had long accepted anonymity as their lot and whodunnits’d grown accustomed to struggle and poverty, now found themselves the happy recipients of media coverage and an upsurge of gig requests. A fan base grew quickly from among the native Egyptians and the foreigners who lived among them. But the infrastructure for the growth of this sector of the music industry was not there, and without it independent music remained clandestine.

Conventional models of music creation and promotion are designed to make more money for the upper turrets of the music industry than for musicians, supporting just enough superstars to make a music career seem so attractive to up-and-coming musicians and composers that they’re willing to give over too much money and control to the enterprise. But in Cairo, several independent entertainers decided to extend their maverick approach from making music to making a living.

?There’s a great guitar player in Cairo now,? says Nour, ?called Ousso. He has a diploma in guitar from America and he plays in Eftekasat, the most incredible jazz band in Cairo. Ousso had a unique idea that ended up being good for all of us. His idea was to have an underground concert. He came up with a really good business model to make this happen. It was called the S.O.S. Music Festival. Because of it, the underground bands in Cairo got more famous. The musician takes 50 per cent of the money.?

?When the revolution came it actually gave us more opportunities, even television exposure. It was an amazing experience for me, the first time I sang before millions of viewers?something I had only dreamed of.?