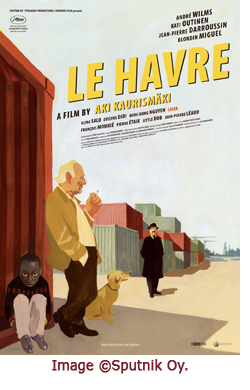

Film: Le Havre (Janus Films 2011)

Film: Le Havre (Janus Films 2011)

Writer/Director/Producer: Aki Kaurismäki

Cast: André Wilms, Kati Outinen, Jean-Pierre Darroussin, Blondin Miguel

?Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it.?

Hebrews 13:2 (NIV)

God Smiles on Port City Ghetto Saints

Marcel’s wife, Arletty, is in the hospital to undergo a series of cancer treatments. On his way home Marcel is stopped by the grocer, who just the day before had read him the riot act for not paying his bill. Today the grocer, knowing about his wife, tells Marcel he has some groceries that are going bad. He’d like Marcel to take them off his hands, if he wouldn’t mind. He then proceeds to pull items off the nearby shelves and load up a box with canned goods and dried beans.

It’s the sort of random act of kindness Marcel has come to expect and is just as ready to dole out. When he accidentally meets Idrissa, a boy refugee from sub-Saharan Africa, it never occurs to him to deny the boy’s needs (even though his concern for his wife would certainly give him an excuse to look the other way).

Marcel and Arletty have lived for years in a bleak little house on a bleak street in a bleak neighbourhood in the fishermen’s quarter of the French port city, Le Havre. The neighbourhood is populated with the kind of dishevelled, good-hearted people who have little but who always find things to share, folk whose religion is humility and compassion. Happy the individuals who fall into such hands in their hour of need.

Marcel himself is a former Paris bohemian who now shines shoes for a living, a singular mission considering the number of rubber boots and running shoes that keep crossing his line of vision. Far from feeling humiliated, he takes pride in how this trade affirms, as he says, the Sermon on the Mount.

When he dresses up he looks quite handsome and distinguished and easily fools officials into thinking he’s of a higher station. In one scene he’s trying to get some information about Idrissa’s family from an anal-retentive bureaucrat:

OFFICIAL: His brother? Are you mocking me?

MARX: I’m the family albino. And unluckily for you, a journalist and a lawyer. Know what the law says about discrimination based on skin colour?

OFFICIAL: I never?

MARX: [palm raised] don’t make it worse. [patting coat pocket] I recorded everything.

Arletty has devoted her life to the kind and gentle Marcel. Though she appears cold, we see her diligently perform many little tasks to make his life easier, even shining his shoes so that he, the shoe shiner, won’t have to do it himself. We learn that her first husband was abusive, which may explain the frozen visage, common to those with PTSD, that comprises her strange composure.

Idrissa, the young refugee, is a wonderful character who plays straight man to the crude flamboyance of the Le Havre locals. This is actor Blondin Miguel’s movie debut, and It’s a phenomenal one; his gentle dignity and thoughtful expression are transcendent. He seems like an angel sent to test these folk, his ultimate blessing dependent on the number and quality of their acts of mercy.

The tenderness with which writer-director Kaurismäki presents these people is a far cry from the racist aspersions we’re used to hearing against the French, but it seems that It’s the French bourgeoisie and upper classes that are most often found guilty of xenophobia and exclusivity. Kaurismäki has said he can’t write for the middle and upper classes?he simply wouldn’t know what they’d have to say.

Is he wearing rose-coloured glasses? Maybe; those of us who’ve grown up among the working poor know there’s no dearth of bigotry, violence, and apathy among them, but there’s normally much less hypocrisy here than in the higher castes. And we’re all familiar with the statistics that show that the lower the income, the higher the percentage of that income That’s given to those even needier.

Kaurismäki loves to include musical performances in his films, and this one features Le Havre rhythm and blues icon Roberto Piazza (also known as Little Bob), playing himself. Other musical references in the film point to the international network of African musical influences that inspire us today. At the refugee centre, an African man in a dashiki is plucking a sintir. Later we see Idrissa listening, mesmerized, to a Robert Johnson record on Marcel’s battered old phonograph. The still rapture of this victim of political violence, on a quest to find his mother, is heart-rending.

Le Havre manifests seven of the Mindful Bard’s criteria for films well worth seeing: 1) it is authentic, original, and delightful; 2) it harmoniously unites art with social action, saving me from both seclusion in an ivory tower and slavery to someone else’s political agenda; 3) it provides respite from a sick and cruel world, a respite enabling me to renew myself for a return to mindful artistic endeavour; 4) it inspires an awareness of the sanctity of creation; 5) it displays an engagement with and compassionate response to suffering; 6) it renews my enthusiasm for positive social action; and 7) it makes me appreciate that life is a complex and rare phenomenon, making living a unique opportunity.

Wanda also penned the poems for the artist book They Tell My Tale to Children Now to Help Them to be Good, a collection of meditations on fairy tales, illustrated by artist Susan Malmstrom.