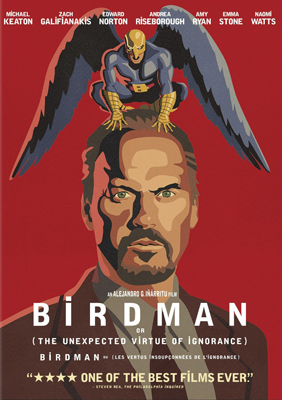

Film: Birdman (or “The Unexpected Virtue Of Ignorance”)

Film: Birdman (or “The Unexpected Virtue Of Ignorance”)

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

“And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so?”

“I did.”

“And what did you want?

“To call myself beloved, to feel myself beloved on the earth.”

– Raymond Carver in Late Fragment.

What you hear at the start of this film are first the voice of the hero’s alter ego, Birdman, and then the doo-DOO-doo ring of a Skype call. The voice of Birdman is contemptuous and mocking, and the Skype call ring sounds just as invasive and grating as it does in real life.

Riggan Thomson, played by Michael Keaton, goes to his laptop and accepts the call. Among the assorted items sitting beside his laptop is a small, shrivelled skull, an object you often see in European paintings toward the end of the Renaissance; it was how artists asked: “Is that all there is?”

Riggan is the actor who portrayed the superhero Birdman in a series of three Hollywood blockbusters. (Yes, Birdman is a thinly disguised version of the Batman role Keaton played, and we can only guess at how much of Keaton’s personal history influenced the story). When Riggan is alone, the Birdman in his head convinces him that he has superpowers like telekinesis and flying, delusions that buttress Riggan against his own profound self-loathing and hunger for love. However, as his daughter points out, his neurotic urge to attract admiration often sabotages his need for authentic connection. “It’s what you always do,” she snarls; “you confuse love for admiration.”

The voices and temptations to delusion are especially intense now. He’s risking all of his resources?personal, financial, and relational? to produce, direct, and act in his first stage play. The stress is almost more than he can bear.

Riggan’s social context is just as absurd as his inner life. His daughter, Sam, in recovery from drug addiction, tells him that he doesn’t exist because he doesn’t read blogs, use Twitter, or even have a Facebook page. His second lead actor tells him he doesn’t exist except as a pop culture superhero. The people who recognise him on the street adore him but don’t even know his name, seeing him as only the actor who played Birdman. His struggle to establish an authentic identity often meets with the harshest of social punishments.

The play he’s producing is Riggan’s version of Raymond Carver’s short story, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” Why is Riggan, after years of incredible Hollywood success, killing himself to produce this play? For one thing, he’s realised that he’s not Birdman, in spite of his fans stubbornly viewing him as nothing but. He’s a real actor and doesn’t want to go down without producing a legitimate work of thespian art.

The ambition to create real art after decades of pandering to the masses makes Riggan especially vulnerable to the temptation to enter his “hero” compartment, that part of his mind where he shuts out reason and moral obligations for the sake of his own egotistical interests. His alter ego, Birdman, works very hard to draw him into this compartment, because without Riggan’s permission, Birdman can’t exist. And so the voice of Birdman continues to mock, threaten, and insult Riggan whenever Riggan tries to be real; the more profound the humiliation Riggan feels, the greater the delusions of grandeur needed to quell them.

(At one point Birdman gives voice to the boast of grossly inflated egos everywhere: “You are a god:” at once a battle cry and a death wish.)

Riggan really is special and marvelous?not as Birdman or as any other character he’s ever played?but as himself. He’s heroic in his intention to turn away from the package of lies, the artifice, the moral blindness, and the self-destructive tendencies that come with pop culture celebrity. He’s heroic in his decision to make real art as opposed to catering to the baser tendencies of baser minds. And he’s heroic in his desire to restore authentic relationships in his life. Riggan is brave enough to ask life for a package of miracles.

The cinematographer employs a remarkable innovation: long, continuous camera shots (as opposed to the rapidfire angle and scene changes we’re used to). The normal human way of seeing things is finally being honoured, that is, we’re not being lead around by the nose by someone else’s vision. It feels like we’re there in the room, our minds wandering, checking out the furniture, listening to the dialogue with one ear and the subtext with another, and just letting the experience wash over us.

Actually, the longshot isn’t entirely innovative. Hitchcock used the technique in his 1948 experimental film Rope. The effect of Birdman is very Hitchcockian, because with this technique, once you start filming, the dialogue can’t be changed (Hitchcock was known for revising his scripts to perfection by himself and then refusing to change a single word during takes). This gives scenes a gritty realism and and at the same time a classical polish.

Another Hitchcockian element is the use of highly symbolic details (e.g. roses, skulls, a tattoo of a serpent eating its tale) which enhance and deepen the significance of the film but which (as Hitchcock complained) are lost on most viewers.

In the absence of scene cuts, the soundtrack provides clues to changes within the psychological process. We hear, for example, the brilliant drum scores of Antonio Sánchez in the theatre when real artistic work is being sweated out, but classical pieces (including, significantly, the romantic composers Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky) during times of fantasy, transcendence, and epiphany.

Birdman manifests eight of the Mindful Bard’s criteria for films well worth watching.

– It’s authentic, original, and delightful.

– It poses and admirably responds to questions that have a direct bearing on my view of existence.

– It stimulates my mind.

– It provides respite from a sick and cruel world, a respite enabling me to renew myself for a return to mindful artistic endeavor.

– It’s about attainment of the true self.

– It displays an engagement with and compassionate response to suffering.

– It makes me want to be a better artist.

– It makes me appreciate that life is a complex and rare phenomenon, making living a unique opportunity.

The Mindful Bard owes much to the tireless research assistance of Bill Waterman.

Wanda also penned the poems for the artist book They Tell My Tale to Children Now to Help Them to be Good, a collection of meditations on fairy tales, illustrated by artist Susan Malmstrom.