What is postmodernism, you ask? Let me share an illustrative anecdote:

A tale of two solitudes

On one fine day back in the nineties I was having a conversation with a woman of both Native American and African American descent. For some reason the topic had come around to how people on the West coast were different from people on the East coast—more adventurous, individualistic, extroverted, egotistical even, than their reserved, stolid, sterling character cohorts in the East.

“I suppose it all comes down to history,” I mused. “When the European settlers started arriving, the more traditional, communal types put down roots in the East and stayed there, while the more curious, brave, and creative pioneers moved West.”

I was thinking in a purely linear fashion: This, that, and the other thing are happening now because of the historical timeline that lead up to them. Makes sense, right? Wrong.

She smiled gently and replied, “I suppose I see it from the perspective of my own ancestors.”

I immediately knew what she meant and was suitably humbled. Having thought of myself as typically postmodern, I thought I’d internalised the understanding that we all come from different backgrounds and that no one group should dictate the history, values, and morals of the others.

It hadn’t occurred to me that her historical context was totally different from mine. Many of her ancestors had arrived from the West and moved East. Others had been brought by force to the southeast and had thereafter moved north. In her worldview, blaming history for making Westerners creative but uncivilised and for making Easterners disciplined but dull just didn’t apply.

Losing the linear or gaining the circular?

Postmodernism is sometimes described as the loss of a culture’s ability to to think in a linear fashion, but I tend to think that we’ve gained an enhanced ability to understand reality, progressing to a way of thinking that’s more like a mindmap or a Venn diagram than a historical timeline.

Things still happen in lines, yes, but in multiple lines all radiating from the hub of the present, which turns out to be the product of many streams of influence. Needless to say this renders the idea of “progress,” at least as defined in modernist terms, obsolete.

No external measure of truth

In addition to respecting multiple viewpoints, another important element of postmodernity is the questioning of hierarchical power. Few people can now say with any conviction that parents, teachers, the church, the justice system, rulers, or, for the purposes of our present exploration, record companies, should be obeyed without question. We know too much now, and besides, the trust is gone.

What this means is that the individual sees herself as the highest authority on her own truth. In a way this is no different from the the beliefs of our ancestors; even those who dictated obediance to the law were doing so out of a conviction that existed within their own skulls. Carl Jung was right, after all, when he said that the only means we have for discerning truth is the human brain—a highly fallible instrument, to say the least.

What this means for postmodernists is that individuals can’t easily be compelled to trust outside sources of “truth,” and there’s no external measure by which degrees of truth can be determined.

In its ideal state postmodernism is a balance between groupthink and individual think, a new social model in which every individual viewpoint is given equal weight and no one viewpoint is allowed center stage. A ridiculously tall order, but aiming for it does engender an interesting array of personal stances, ranging from a more authentic valuing of our fellow creatures to a sense that since no one matters more than another, no one really matters at all.

What does postmodernism mean for music?

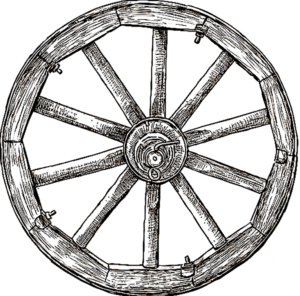

If we were to try to explain the postmodern experience of music to a modern from the past, we might get them to imagine themselves at the centre of a wheel with spokes, representing different musical histories, radiating out in every direction. At the hub of this wheel every genre of music is simultaneously available for listening or performing.

If we were to try to explain the postmodern experience of music to a modern from the past, we might get them to imagine themselves at the centre of a wheel with spokes, representing different musical histories, radiating out in every direction. At the hub of this wheel every genre of music is simultaneously available for listening or performing.

They would soon understand why genres are now mixing and morphing so fast that even the idea of genre is becoming obsolete. They might also understand why there’s no one musical “scene” that everyone feels constrained to follow.

So what do we have now? What special knowledge can we gain from standing at the centre of this strange new wheel, in which early medieval polyphony and Balinese gamelan music are no further from our ears than Beyoncé? What special insight might postmodernism grant us into the nature of music itself?