At a birthday party a professional virtual reality gaming crew arrived in a van; they handed us plastic boxes to put over our heads and the entertainment began. Soon everyone was in fine digital gaming fettle, battling terrorists and rescuing damsels and defeating all comers in a wrestling ring. At first it felt weird to put on the headcover—an ontological shift into cartoon ostrich status, but in fact it was less claustrophobic than being in many an indoor gathering, pandemic masking or not. I mean, who hasn’t sought an excuse to leave a room for a breather from society? Nowadays that’s when we end up checking our social media newsfeeds, starry nights ignored.

At a birthday party a professional virtual reality gaming crew arrived in a van; they handed us plastic boxes to put over our heads and the entertainment began. Soon everyone was in fine digital gaming fettle, battling terrorists and rescuing damsels and defeating all comers in a wrestling ring. At first it felt weird to put on the headcover—an ontological shift into cartoon ostrich status, but in fact it was less claustrophobic than being in many an indoor gathering, pandemic masking or not. I mean, who hasn’t sought an excuse to leave a room for a breather from society? Nowadays that’s when we end up checking our social media newsfeeds, starry nights ignored.

Self-imposed timeouts have become more and more necessary as our society has whittled and winnowed away our splendid, thoughtful, isolation. So much so, that many of us have our 3.5 inch smartphone screen reclined on the bedsheet next to our pillow, like a beloved stuffed animal, as we drift off to sleep. Something deeper might be going on than sheer addiction or obsessive connection with others (that rang true for young lovers since the first phone lines were clogged with overuse). Pondering the social significance of this new emergence, a far cry as it is from the fleeting joys of a Viewmaster® camera, a clarity about the value of being unstimulated emerged.

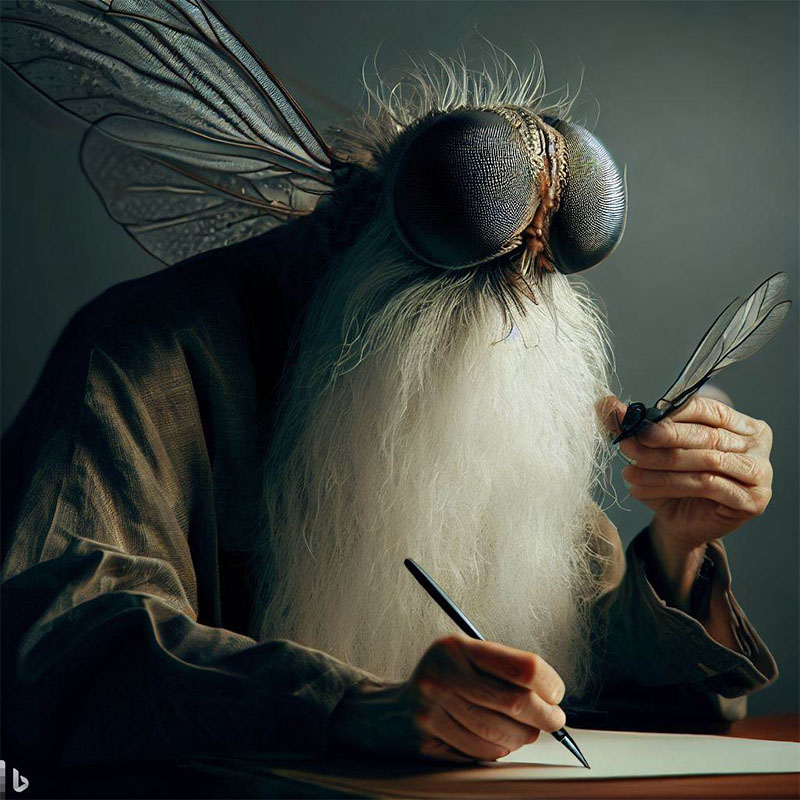

While most folks used their time with the VR gear strapped over their noggins to shoot various weapons and be the first-person hero in the action movie of their dreams, my wife and I took the opportunity to merely float in a pleasant digital tropical lagoon—a believable 3D life aquatic, easy on the stressful cortisol levels and pleasant to eyes and ears. Not much happened plot wise in those digital waters, other than that the occasional dolphin or lamprey or boxfish would swim by—but that was the point. A space of ideas emerges precisely when the backdrop, the context, contains openings for new thoughts to rush in. Like a childhood sandbox with a hose ready to create some weather events perchance to wash away a few toothpick villages, the mind channels what comes into it but also, sure as sugar, comes up with its own idea of angels and monsters and the manner of their personal demonstration. We need mental blankness so that new concepts, new miasmas of the mind and conceptual chiasmas and chimeras can emerge.

Over-walloped though the dead horse of addressing our micromanaged and overstimulated digital subjectivity here in the 2020s may be, the abject lack of time to gaze off into mind-wandering imaginative space perhaps cannot be overstated. We might know that the world is awash with mindfulness memes implying that we should stop right there with the doom scrolling, but do we do much about it? Maybe what’s required is an echo chamber box that blocks out all stimulation: a simulation hypothesis for a mental reprieve from reality,

A little digital float inside the cognitive echo chamber of the virtual reality headgear reveals the irony that this prized form of entertainment begins with the psychological desire, perhaps even a need, to box out all the external world to have a good time. Reduced to a state of blindness that would make any bat quiver, easily disoriented to the earthly realm of gravity and coffee tables, a not uncommon thought calcifies: Why is entertainment expected to add stimulation to our lives when it could provide a gentle relief, a coral reef however brief, from the intrusive onslaught of disturbing data and emotional conflicts that beset so much of modern life?

To be sure, the creative arts do function best when they draw us into their realm and encourage us to lose ourselves peacefully, without a struggle as it were. Inexpensive wall posters often implore us to enter into their visual realms; in fact, most visual art literally draws us into its open-ended nowhere by means of the vanishing point (the horizon point in the art to which the mind is drawn). Nevertheless, the incessant urge to do something, to experience something, drives us onward like Maoist soldiers seeking communist salvation during the Long March (where hundreds of thousands of Red Army troops, having been routed, 1 500 kilometres through farmland and mountains). “Speaking of the Long March, one may ask, “What is its significance?” We answer that the Long March is the first of its kind in the annals of history, that it is a manifesto, a propaganda force, a seeding-machine.” That perpetual and unrelenting action, often dubbed productivity, is the wellspring of good works remains a cardinal tenet of modernity, and likely underpins the sensation that by sitting with our screens we are at all times doing something, keeping busy. In this sense, the escape provided by academia may not abet deeper existential challenges—unless we pause to ponder the void into which our consciousness slips when we aren’t constantly thinking about something, stimulated by demanding inputs.