You can’t Bury Them All

You can’t Bury Them All

poems by Patrick Woodcock

“I sit in the palms of the street beggars you ignore,

cover myself in grass and straw to watch mothers,

unlike you, mourn. I sit on the back of seagulls

defacing your monuments.”

– Patrick Woodcock, from the poem “I sit on the backs of seagulls,” in You can’t bury them all

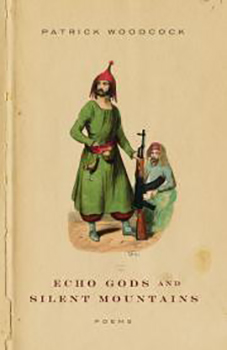

Patrick Woodcock has long documented human experience in colonised, occupied, and war-torn regions of the world. His poems are a kind of poetic nonfiction which have been described as travelogue poetry but which I prefer to call journalistic poetry. (See the Voice review of Echo Gods and Silent Mountains: Poems, his book of poems based on his time in Iraqi Kurdistan.)

Woodcock speaks eloquently for victims, and we hear the judgment pronounced against their enemies from their own mouths, not his; here the poet’s role is more that of a chronicler than a hero.

He speaks for the native elders of Fort Good Hope in the Northwest Territories who are grieving the loss of traditions and respect that are no longer being passed on, and the lack of influence they’re allowed to exert on their communities.

He speaks for Zaur Hasanov, the Azebaijani veteran who burned himself alive to protest the government’s destruction of his restaurant. He speaks for the kindly Kurdish Muslims whose liquor store was demolished by extremists. (“There were hundreds of men?” Woodcock writes, “only men.”) He speaks for the little girls forced to weave the lovely Persian rugs that are more highly valued than the girls themselves.

In spite of the suffering he records in his poems, many of the scenes Woodcock describes are so magically, touchingly beautiful that they force you to stop and breathe slowly, to become fully aware of the significance of what You’re seeing. This is a world where statues beg you not to blacken their marble linen folds, where tree trunks dance and fall into orchestra pits, where the sun is punctured and hisses as it deflates, where a pile of rubble is compared to “a giant’s afterbirth.”

The following is a passage from his prose poem, “Welcome to Sharia Municipality:”

. . . This abundance of simulated

suns, and its refusal to blend and mingle politely

with the galaxy of particles enshrouding me, in-

duced hallucinations. Horses galloped at me

through clouds of hailstones. My taxi bucked and

whinnied. Little girls in rowboats glided upon

rivers of snakes toward me.

And yet he’s humble enough to let himself channel the charming simplicity of the great northern verse masters like Robert Service, as he does brilliantly in “Abandoned at Charlie’s cabin to take inventory.”

In You can’t bury them all the poet doesn’t have a conspicuous role; occasionally he’s the one helped, the one acknowledged, the receiver of touching kindnesses, but mostly he’s the silent witness who continuously and painstakingly cultivates his own sensibility in order to honour, as best he can, the profundity of the anguish before him, never dishonouring the suffering by interfering with it. His lens frames what matters most, just as chroniclers of ancient wars told you only what mattered?that is, what would still matter in another millennium.

Patrick Woodcock is still a literary nomad. He’s still a salient metaphorical mouthpiece for the ancient world of magical incantation. Although the self as witness is often hiding within the bricolage of the worlds he describes, there is a kind of story arc here: After the piercing awareness of the hurt caused by human depravity the world over, he recognises that the “home” he returns to is a part of the place “where point five percent of the village hide from the neighbors they pillage.” He calls it “The Great Green Monarchy.”

He then gratefully acknowledges that he himself doesn’t bear its sins.

You can’t bury them all manifests eight of the Mindful Bard’s criteria for books well worth reading.

– It’s authentic, original, and delightful.

– It poses and admirably responds to questions that have a direct bearing on my view of existence.

– It’s about attainment of the true self.

– It inspires an awareness of the sanctity of creation.

– It displays an engagement with and compassionate response to suffering.

– It makes me want to be a better artist.

– It gives me tools of kindness, enabling me to respond with compassion and efficacy to the suffering around me.

– It makes me appreciate that life is a complex and rare phenomena, making living a unique opportunity.

Wanda also writes the blog The Mindful Bard:The Care and Feeding of the Creative Self.