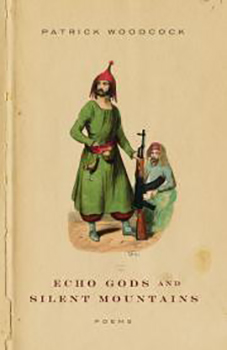

Patrick Woodcock uses poetry to document the suffering of humanity in war-torn countries?a kind of poetic nonfiction. (See Voice review of Echo Gods and Silent Mountains: Poems, his book of poems based on his time in Iraqi Kurdistan.) Recently he took the time to answer Wanda Waterman’s questions about recovering from witnessing suffering, what it’s like to live among Kurds, and the necessary conditions of his creative life. (Also read the first, second, and third parts of this interview.)

Patrick Woodcock uses poetry to document the suffering of humanity in war-torn countries?a kind of poetic nonfiction. (See Voice review of Echo Gods and Silent Mountains: Poems, his book of poems based on his time in Iraqi Kurdistan.) Recently he took the time to answer Wanda Waterman’s questions about recovering from witnessing suffering, what it’s like to live among Kurds, and the necessary conditions of his creative life. (Also read the first, second, and third parts of this interview.)

Recovering from Scenes of Suffering

I’m not sure why, but for some reason I’ve had a few problems coping with things this year. Images that didn’t bother me too much at the time have reappeared in dreams and nightmares and really thrown me off for a few days at a time. And although the Kurdish North of Iraq did have its moments, Fort Good Hope (Northwest Territories) and Azerbaijan have been far more unsettling for me.

I visited a couple of children’s cemeteries outside of Baku, Azerbaijan, to take photographs, and now I really wish I hadn’t. There’s a city north of Baku called Sumgayit. A colleague had told me that it had a large children’s cemetery. Because of the enormous amount of industrial pollution in the city, it had an incredibly high rate of stillbirths, miscarriages, and children born with birth defects. The infant mortality rate was also very high.

So I paid a taxi driver to take me there, but he got lost and after asking for directions took me to the wrong location. I ended up in a small town called Saray and was directed to the corner of a cemetery there. It was obviously incredibly sad to think there was another cemetery for children. As I walked around taking photos of the stones and chipped pieces of wood that stood as tombstones. I noticed a hole in the ground. It was about the size of a rabbit hole?there was nothing else around it?no gravestone or marker. So I stuck my hand and camera down inside it and took a few photos to see what was inside. It was an extremely bright day so I could not tell what I took a photo of by just looking at my camera’s screen.

After returning home, I uploaded the image and realised it was of an unmarked grave?the hole led to a small child, curled up and wrapped in a white sheet. It’s such a sad photo but I can’t “un-take” it. I dreamed about that child for weeks afterwards and have two new poems about that day and its outcome in my new book.

Experiencing Kurds

I’ve met three men in my travels who’ve had a profound impact on my life. The first was an ex-girlfriend’s father in Poland, a wonderfully eccentric man and the leader of the Solidarity Party in his province. The second was my friend’s father in Duhok. He was 82 when I first met him. He had suffered two strokes and a life of misery at the hands of Saddam Hussein. He was a peshmerga?a freedom fighter?for most of his life. He was such a kind and gentle man. Watching him pray in the mountains just outside of his village?a village that had been gutted?was one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen.

The poem “More Than Mountains” was written for him. I was happy to learn that it was translated into Kurdish and read to him and that he really enjoyed it. I actually have a lot of close friends in the Kurdish North who I speak to every month. And I have developed quite a nice friendship with the Kurdish writer, Ava Homa, who is now living in Canada but is originally from Iran. Although I’ve made many friends over the years in numerous countries, there’s something unique about my Kurdish friends that I really cherish. I’ll leave the third man for my next book.

Necessary Conditions of Creativity

Over the last two years I’ve made a very conscious effort to simplify my life as much as possible.

Both my writing and my health are very intertwined?one heavily influences the other. For me, poetry takes a lot of time, patience, and kilometres. I need to buy as much time as possible so I can accomplish what I want to. After that I can nod off.

I’ve never understood the western “Die young and leave a beautiful corpse” mentality. Why? What have you seen? What have you learned? What have you given back? I want to die as old as possible and leave a corpse so weathered and scarred with stories that anyone who sees it would regret not having sat in a pub with me.

When I first moved to Poland I was 24. One of my closest friends was an eccentric British expat in his late 60s. To be with him was better than sitting in the cinema or the best of galleries. I miss him and his anarchic tales very much. He was a sad oddity, but lovely as well. I was there the day he drank 15 beers only to find out when he paid that they were all non-alcoholic. The rage was pure poetry.

Next

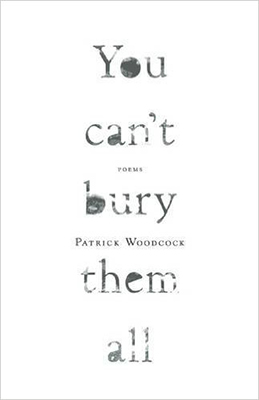

My new book is entitled You Can’t Bury Them All and will be published in 2016. I think this is the first book that I actually “get.” I’ve never had this before?this sense of clarity as I write. All of my other books were a puzzle right up to the end. You Can’t Bury Them All will contain between 100-110 poems, as well as a one-act play. Geographically it will begin in The Kurdish North of Iraq and then move to Fort Good Hope in the North West Territories?a small Dene community of 500, 20km south of the Arctic circle, where I volunteered with the community’s elders for almost 11months.

It will end in the Caucasus?mainly Azerbaijan?where I’m living now and will have lived for two years. In it I’m trying to address all of the “thems” that individuals, societies, and governments try to suppress. I’m not only talking about those who suppress the suffering they have been through due to their age, social status, birthplace, economic downfalls, geographical locations, faith, skin colour, sexual orientation, etc. but also those who naively suppress their happiness and prosperity?hello Canada?and who then try to convince themselves that they have had a difficult life and are still “suffering.”

I’ve sat with people in Canada who are extremely prosperous and healthy. As parents, they know that their children have access to far above average health care and all the educational and vocational opportunities in the world. They wake up daily to a life full of possibility. But they’re also the most miserable, whiny pricks I’ve ever had to suffer listening to. I’m not saying that Canadians have no right to complain?of course we do, and because of our privileged status we should actually be complaining and railing more. But the objection should be more than a theatrical moan?it should be an honest attempt at improving the world, not the pathetic internalised self-pitying bullshit I hear so often now.

(Patrick Woodcock’s Tumblr page. Echo Gods and Silent Mountains can also be found here on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Echo-Gods-and-Silent-Mountains/248778701905472)